Why does delivering infrastructure have to be so complex on so many different levels? It seems hard to correctly identify infrastructure, assess the need for services from those assets, discern which infrastructure to maintain, rehabilitate, replace or build new. Further, there are strong disagreements at the political level, between infrastructure agencies and, within infrastructure agencies, between different asset managers.

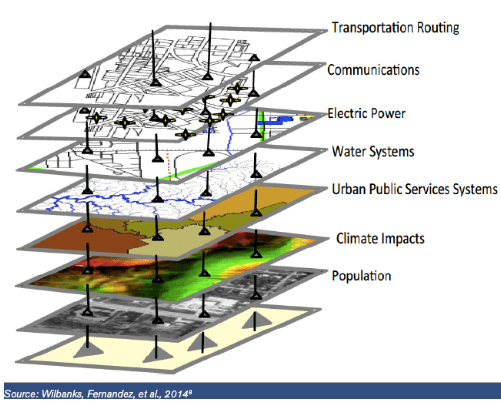

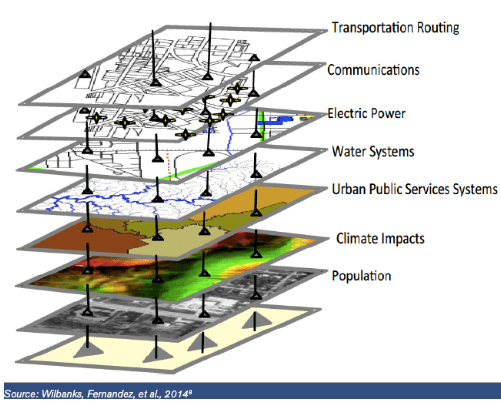

Complexity arises from the involvement of a broad array of participants in the provision of infrastructure assets, as well as the managers of the services provided from those assets.

It also arises from complex streams of benefits. In addition to benefits accruing to consumers of infrastructure services, there are often significant streams of benefits that are positive externalities. Wider benefits to society from improved health services, better access to education, cleaner water supplies, stable supply of electricity, and improvements to travel time and quality of the trip. A healthier workforce improves productivity. A more educated populace can generate higher disposable incomes. Purer water supplies enhance public health. Stable electricity supplies reduce business interruptions. Improved transport systems make labour markets function better and increase intra and inter city productivity. The benefits are multifaceted and often hard to quantify on cost-benefit analyses.

On the supply side, it is often too easy to overlook the range of solutions that are on offer. After a need has been identified, solutions could well include non-built options. This may involve active demand management, improving utilization and output of existing assets, repairing and rehabilitating existing infrastructure, changing the infrastructure asset operating environment to foster demand for alternatives.

The options analysis needs to be undertaken at the output/outcome level, rather than at the input/resource level. That is where actual economic value can be identified. To do otherwise creates the risk of estimating the cost of sub-optimal options.

Complexity also arises in terms of finding the financial resources to commission and operate infrastructure assets. Also, implementation through procurement and construction may have complexity.

Large, nationally significant infrastructure contains a lot of first pass risks. Getting the right scale and scope of infrastructure to match the most likely demand profile requires a lot of analysis.

Many infrastructure assets contain hiding optionality benefits. The ability to set the ultimate scale and scope, as well as the possible staging to achieve that is a significant real asset option. At the outset, a lot of choices can be made that close off options later on. Least cost solutions are not necessarily the best solutions where service quality between options can vary.

So what gets bought and how it gets built becomes critical.

Ultimately financial resources are committed. This is because small annual benefits are often realized over long periods. This is in contrast to large initial construction costs. Construction costs and some measure of operating expenses have to be funded. User charges do not always cover these costs. Finance addresses the imbalance of cash flows inherent in infrastructure. Ultimately, infrastructure must be paid for either by users or taxpayers. There is a significant range of public and private financing mechanisms. Financing choices are complex and can carry different risk profiles. This can affect asset valuation, as well as commercial risks around viability.

These are all significant touch points highlighting infrastructure complexity. They warrant detailed consideration and investigation in each infrastructure project.

Value capture and uplift associated with infrastructure projects are often discussed but not well understood. This is because the issue sits at the crossroads of competing public and private interests, as well as institutional imperatives of project proponents.

Value capture and uplift associated with infrastructure projects are often discussed but not well understood. This is because the issue sits at the crossroads of competing public and private interests, as well as institutional imperatives of project proponents.